SALT VERY IMPORTANT

The Milky Way’s Huge Black Hole: April and May Letter from Literary Arts

Emerging from the colossal black hole we call winter, into slightly less dark, slightly less hole, days of rain in cedar trees, a river valley, wild turkeys on the back road, me, hemorrhaging money to the organic grocery co-op, a little bit high on mushrooms.

So, you found a huge black hole–

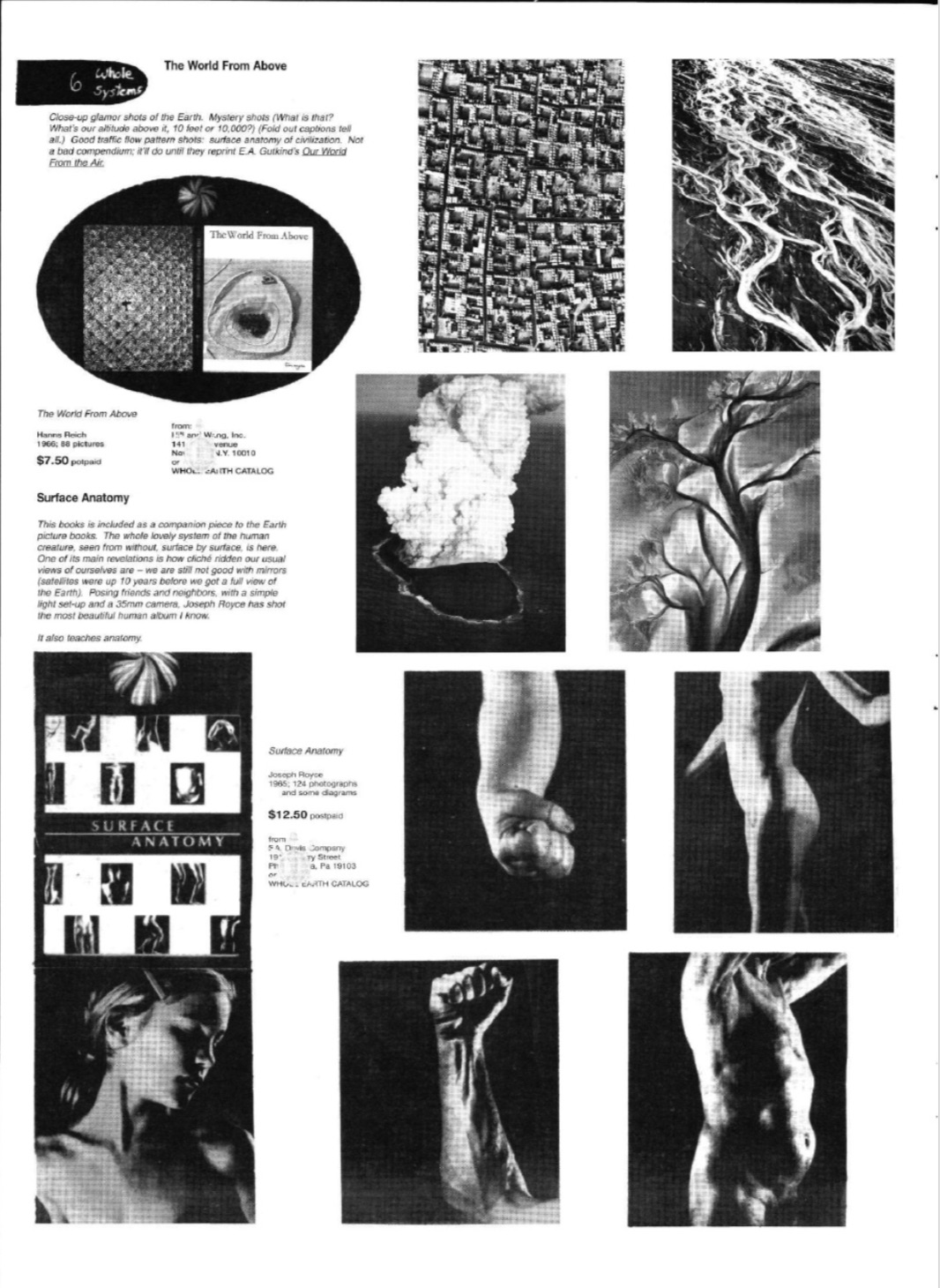

In 1968, Stewart Brand published the first issue of the Whole Earth Catalogue, which featured on its cover one of the earliest images of the Earth seen from outer space. For many, it was an image that inspired a sense of connectivity and shared existence. The photograph made visible the once abstract notion of the Earth as whole, its overlapping systems of weather, energy, and ecologies, bound together by one atmosphere. The awe induced by seeing the earth from outer space is now a well documented psychological response called “the overview effect.” NASA’s astronauts report experiencing an unparalleled mental clarity after witnessing the earth from outer space. I wonder about the effect of these first images of the Milkyway’s huge black hole.

Beyond the sheer pleasure of the headline, the photograph, for me, induces nihilistic fear. How could something be so big, and so far away? And more importantly, what is nothing made of? The black hole puts into question the ontology of matter. How do we understand the existence of matter if it can be sucked into a vacuous gravitational force, the genesis of which was the explosion of a star? The photograph of the black hole arrives in the zeitgeist a phantasmagoric cavern, a visualisation of the void. And for me, seeing the shadow of a black hole doesn’t prevent its unknowability from destabilising my attachment to existence.

As much as holes induce fear, they remain an intriguing site of metaphoric and conceptual inquiry. Sara Maston’s work on hole digging comes to mind, bringing in the perspective of worms–earth eaters and hole diggers among us. The collective Emilia-Amalia ran a year long program called, HOLES AND HOW TO FILL THEM, “that explored historical gaps, omissions, and strategies of refusal and withdrawal as modes of feminist praxis.” The hole, in this case, a site of historical and archival exploration, as well as a methodological approach. I’m reminded also of the artist project in C Magazine 108, Money by artist Abbas Akhavan. what is above is as that which is below, is a photographic collage wherein the artist overlaid gold leaf on an image of a mine, which was overlaid on an image of a gay porn crotch. Money on money hole on money hole.

There are also the poetics of wormhole, rabbit hole, loophole, butt hole, Alice’s wonderland hole, blind hole, sinkhole, pot hole, through hole…

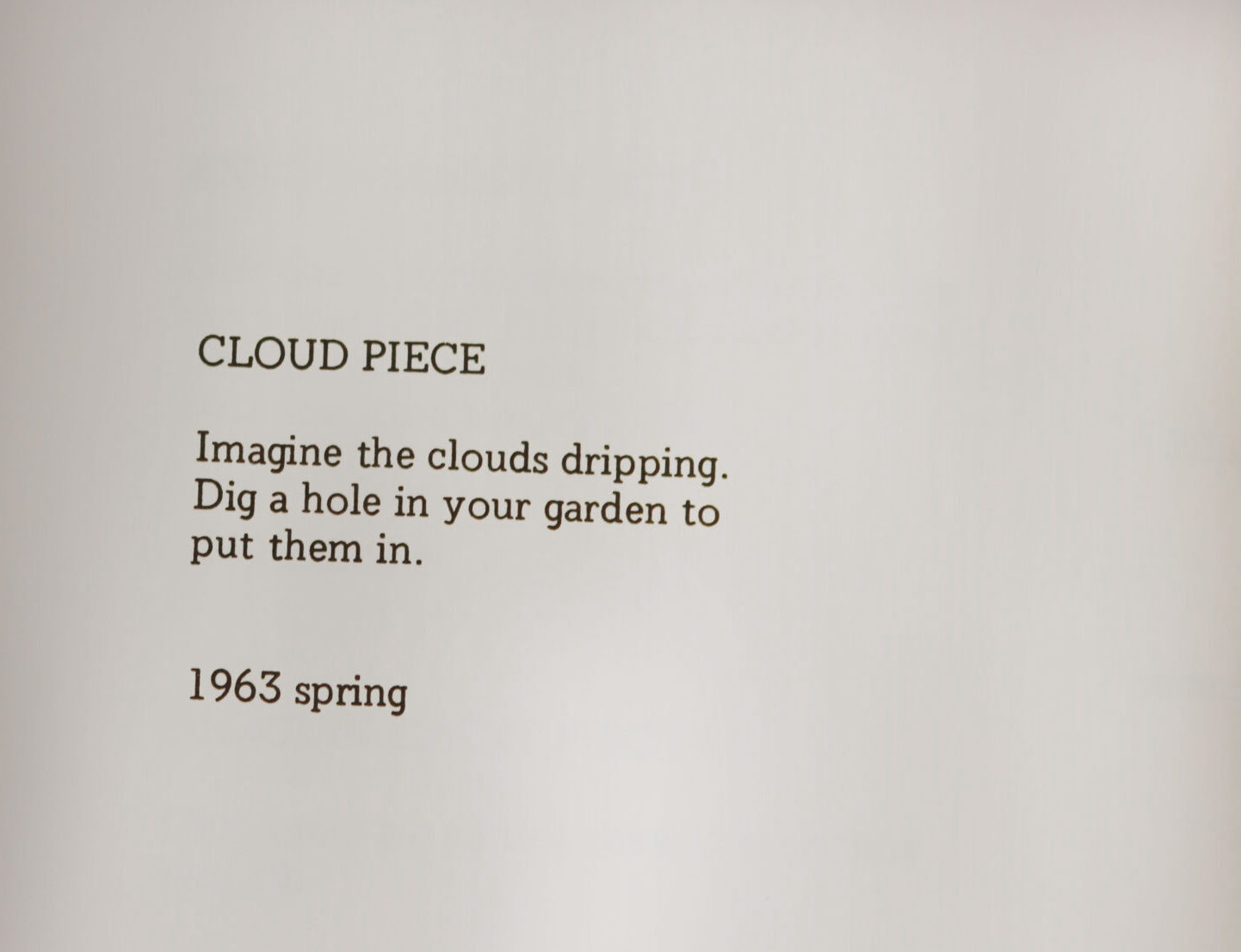

dig a hole in the garden

Taking its name from Yoko Ono’s “Cloud Piece” (1963), dig a hole in the garden is a duo exhibition featuring works by Shannon Garden-Smith and T’uy’t’tanat-Cease Wyss.

Through the deep hibernation of winter, reading Louise Gluck by the woodstove, we re-worked an exhibition proposal designed to emulate the life cycles of tardigrades: torpor, adaptation, hibernation. It was conceived as a winter research project with summer exhibition, wherein moss would be soaked in water to create tardigrade habitats in the gallery. Though our tardigrade plans fell through, we carried over the notions of slowness, rest, rebirth, and seasonal change for our summer exhibition, dig a hole in the garden, which explores processes of plant collection through alchemy, dream sleep, burrows; plants in bud, bloom, and death (I borrow from artist Derya Akay, to whom much of this research is indebted).

Much of the planning for dig a hole in the garden happened in winter, when time is queer, rest is paramount, and the darkness holds us. My winter was marked by sleeplessness due to a recurring bad dream, and by a brief stint working in harm reduction at an overdose prevention and sobering centre. By no means do I want to over state my nightmares or my role in harm reduction work. It was an intense, seasonal job that felt possible only because of my particular geography at the moment, and the relationships I’ve had in that community. Working at the sobering centre put me in conversation with folks with whom I would have otherwise not known, and gave me an active relationship to some of the political theory I have been interested in over the last year: anarchy, mutual aid, and intentional community work.

That direct relationship to folks experiencing the crises of houselessness, opioid overdose, and addiction, informed much of the thinking I did over the winter. I was particularly moved by the stories of a number of co-workers and clients, and learned to carry a deep compassion for those affected by our culture’s pathological moralization of substance use, poverty, and pain. I was also moved by Carlyn Zwarenstein’s words in On Opium: Pain, Pleasure, and Other Matters of Substance (2020), in which she speaks to the overwhelming need for harm reduction operations, and for self-determination and independence in the realm of pain management. One of the most compelling arguments she makes is around seeking autonomy over our pleasure, and how empowering it can feel to use a substance that gives us relief from pain, be it physical or emotional. In a culture of unmanaged and untreated pain, our power lies in our ability to navigate medical and social institutions. Cultures of extraction, imperialism, white supremacy, and capitalism, breed toxicity and injury, with damages sustained over generations. And yet so often, the same institutions that purport to care for us, ask us to perform our well-being by giving up the substances that offer a glimmer of control over this systemic injury. These substances are plants: poppies, cannabis, yeasts (a category of its own). These plants store cultural and embodied knowledges, they have entire ecological systems with niches of their own.

With all of this in mind, dig a hole in the garden, brings together two artists who work with plants at various stages of their life cycles. Shannon Garden-Smith works with plant refuse collected throughout the winter. “In a hare’s form” (2021) suspends plant detritus in translucent gelatin lampshades, lit up in the otherwise darkened gallery. Garden-Smith has also made a suite of gelatin window stickers with plant matter for gallery visitors to take home to place in their own windows. Ethnobotanist and artist Cease Wyss works with plants at all stages, building gardens using permaculture methods and Indigenous ecological practices. Prior to the exhibition, Wyss will collect native plants to create an herbarium in the gallery, featuring stories and objects of the plants’ uses. These works speak to the temporalities of gardens and ecological transformation, the low-light of sleep and hibernation, attunement to seasons and cycles of change. Through material and cultural exploration of plant collection, the exhibition puts into question how plants transform us, and how we might learn to adapt along with them.

dig a hole in the garden will include a library and reading group throughout the duration of the exhibition. The reading group includes texts related to plant use for pleasure, pain management, community resistance and resilience. It will meet Wednesdays 4-5pm PST for five weeks. Details to follow!

Geopoetics Symposium

Geopoetics, etymologically, refers to earth (geo) making (poiesis). It attempts to work in opposition to a geopolitical understanding of place, one that imposes extractive politics onto lived and embodied understandings of place. Geopoetics, rather, is a process of collective speculation. the labour of community building, and an intentional cosmological shift towards an enlivened, enspirited worldview. Erin Robinsong notes in the introductory essay to the symposium that was recently held on Cortes island, “For those of us who have inherited a worldview that perceives the world as insentient, inert matter, along with the extraction and devastation such an understanding makes possible, of course we are looking for new language that recognizes the intelligence, kinship and enmeshment we have with the living world.”

I left the symposium feeling totally immersed in magic. I swam with Astrida Neimanis (sort of), who read an essay about sleep and kelp, referencing Anne Sexton’s The Briar Rose, and Harmony Holiday’s An Artist’s Guide to Herbs. Astrida and I had made plans to swim early in the morning after the final night of the conference, but after Cosmo Sheldrake’s DJ set the night before, I missed our date at the ocean. When I told Astrida I was sorry we didn’t swim together, she said, oh but we did! we shared the same water..

Experimental cello artist, Anne Bourne, was there, who led us through John Cage’s score for 4:33. Rather than silence, we emitted a heart song, placing one hand on our heart and one hand on the back of the person next to us. Everyone let out a hum. You could feel the vibration of the circle through your hand, and in the resonating harmonies. It was a moment of embodying the theory that had been discussed all week.

Of that theory, two things resonated with me: time and borders. What is the temporality of earth making? Maybe slowness, wholeness, attunement, body connected to mind, refusing to write with jargon, a higher valuation of plant, animal, microbial, and fungal life.The land as always connected to people. That Land is Indigenous cultural practices, epistemologies and cosmologies, and any speculation of a future on the Land makes paramount the decolonial methods distinct to that place. And the borders, highly politicized barriers that are so often arbitrary. Who is allowed to set borders and tend to their delineation? Jenny Holzer, “BORDERS DON’T PROTECT YOU ANYMORE,” and, did they ever? Living on our lands as whole and lively beings without fracture of community, geology, ecology. Allowing the fluidity of history to run across lands without settler borders. Might this all be part of a geopoetic agenda?

Although the symposium was an inspiring convergence of minds, it occurred to me when I returned home, that a gathering on the same theme, with farmers, foragers, herbalists, and gardeners, rather than scholars, might yield entirely different conversations. Or maybe conversation would be peripheral to the labour of world building. In spaces of academic practice, there is so often a discordance between embodiment and the theory of embodiment. That dissonance feels particularly poignant within the speculative practices of futurity–there are quite literally people already building the worlds imagined through a geopoetic framework.

Among the facilitators were singer and storyteller, Khari Wendell Mcclelland, choral director, Vanessa Richards, director of the Feeled Lab at UBCO, Astrida Neimanis, scholar and author of Hungry Listening, Dylan Robinson, poets and activists Cecily Nicholson, Rita Wong, Sonnet L’Abbé, and David Bradford, who has been short-listed for the Griffin Poetry Prize, essayist and critic Michael Nardone of Concordia’s Centre for Expanded Poetics, mushroomer and host of the podcast Future Ecologies, Mendel Skulski, author of Entangled Life, Merlin Sheldrake, musician and DJ Cosmo Sheldrake, ink maker and ceramicist Flora Scott Wallace, Nadia Chaney of Time Zone Research Lab, and poet-philosophers, Jan Zwicky, Robert Bringhurst, and David Abram.

SYLLABUS: January, February, March Letter from Literary Arts

After a three month stint in that hole we call winter, I emerge this week of equinox with a few brute and somewhat carefree reflections on a handful of drug related readings. I admit these reflections are written in haste, and to be enjoyed with a lightness of spirit. Should deep, critical reflection be desired by you, reader, please email me, or meet me on that spiritual plane between micro and macro dose.

On Freedom by Maggie Nelson

An illuminating and wide-spanning collection of essays that consider the practice of freedom in four aspects of life: art, sex, drugs, and climate. While at first I was skeptical about the contributions of a white woman to the discourses of freedom and liberation, I am a Maggie Nelson stan (a WW myself), so I read on. I was, at times, made breathless by Nelson’s complicated prose and ability to hone in on the nuanced paradoxes inherent to ethical concerns, including our collective and individual liberty. Nelson never arrives at a conclusion, making her work difficult to summarize. Rather, she entangles us in her thinking, making what at first appears a simple question, a chimera of concerns. Her chapter on art takes up the notion of care in contemporary art practice. She reminds that art doesn’t care; that one of its great gifts is that it cannot mean more than what it is, despite our attempts to imbue it with meaning or suggest that it extends beyond our experience of it. In the following chapter, Nelson offers astonishing insights about the #MeToo movement, consent culture, and treatments of sex in feminist discourse. She complicates our understanding of power, quoting Foucault generously, and invites us to consider the individual responsibility of asking for what we want–a more mutalistic approach to consent culture. The following chapter on drugs acts more as a literature review than a profound discussion of freedom in relation to dependency, the overdose crisis, and housing precarity, possibly the least developed chapter of the book. I’ll admit I was too afraid to read the last chapter on climate change, after already having confronted so much. Maybe in the height of summer, when the heatdome returns, I’ll feel called to think critically about climate. For now, I’m enjoying the peaceful blooms of early spring.

My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Otessa Moshfegh

I read this with feverish urgency. It was like nude descending spiral staircase into depression by Marcel Duchamp’s bimbofied contemporary counterpart. It was 2001 eating disorder propaganda. A vapid, navel-gazing young woman attempts to deal with her parents passing by drugging herself into oblivion. Despite her inheritance, impeccable wardrobe, art history degree, and the ease with which she moves through early 2000s NYC, she hates herself and seeks solace in delusion. Her pill use leads to memory loss, which she relishes. Though a rational and emotionally developed character would understand her depression is inflicted by the loss of her parents and her douche-bag boyfriend’s inappropriately timed blow-job asks, instead the narrator stages a trite art performance that draws on her drug induced amnesia. All the while, her bulimic best friend loses her mother and has an affair, details that remain peripheral to the narrator, until that same best friend dies in the 9/11 attacks on the last page of the novel. I mean, I had to wonder why this novel was so easy to read despite its subject matter, and why it has remained such a popular book since its release in 2018.

On Opium by Carlyn Zwarenstein

An eclectic collection of essays that span the literary and artistic histories of opium, as well as the relationship between harm reduction operations, opioid use, the overdose crisis, and housing precarity. Zwarenstein narrates from the perspective of her own opioid use: Her degenerative spine disease has forced her into a dependent relationship on the drug, a relationship, she says, she tried hard to resist. As the collection goes on, her pain persists, festers, and shifts around her body as her dependency grows stronger. Along with her first person experiences of dependency and addiction, the essays include interviews and snippets of conversations with unhoused drug users around Toronto, where Zwarenstein is based. The book is truly illuminating in its first person depictions of opioid addiction, houslessness, and encounters with treatment services. Its lengthy descriptions of harm reduction operations pinpoints the limitations and effects of these systems on users, and how they might be changed. I think most poignantly, this book taps into the reality of addiction through the lens of pleasure. While not undermining the very real fear, pain, and oppression of addiction–and the myriad complications related to drug policy, housing, and treatment–Zwarenstein reminds us that being high feels good, and that a relationship to opioids is more complicated than just dependency. For some, taking opioids involves, to a certain extent, choosing to enjoy life, despite or within the circumstances. Though at times the essays try too hard to be more than what they are–an object of history, a women writer forging a feminist lineage–the collection is ultimately a necessary contribution to the literary and harm reduction fields.

The Teachings of don Juan: a Yaqui Way of Knowledge by Carlos Casteneda

An almost unbelievable display of colonialism, an ethnographer stalks and forces a Sonora Mexican man to teach him about medicinal plants and the Indigenous cosmology of their teachings (I’m being inflammatory, but, this is the gist of it). The stupid white man rolls around on the floor for hours before don Juan agrees to work with him—having succumb to a display of ridicule. Casteneda enters the research through academic means, and ultimately attempts to describe teachings and experiences that are sacred and were previously not available to the public–especially not to the public of white hippies in the 1960s who flocked to this book as a bible after it was mentioned in the Whole Earth Catalogue, and who consequently began munching on peyote like popcorn. Core to Casteneda’s narrative is a dilemma in his attempt to fit his stories into an academic ethnographic account, a problem of how knowledge and logic are ascribed in Western thought. Casteneda assumes a more circular narrative as opposed to linear, and forges on to divulge the intricacies of don Juan’s teachings as well as his own experiences on the medicinal plants he’s ingesting. While Casteneda’s work is now largely considered a work of fiction, still the dilemma in his narration poses a contemporary question of epistemicide. When knowledge and teachings are consume so widely by a white audience, what comes of the context, specificity, and sacred nature of that knowledge? What happens to the people who practice and teach that knowledge when it is extracted for consumption? The notions of opacity and refusal in relation to Indigenous knowledges are much more prevalent now than they were in 1968 when the book was published. It reminds how delicate systems of knowledge, land and spirit are, especially in the wake of colonialism, capitalism, and the byproduct of these two–resource extraction. On a cultural and critical level, it doesn’t stand the test of time; on a narrative fiction level, I problematically consumed its contents with pleasure.

Accidental Eden by Douglas L. Hamilton and Darlene Olesko

A local history project written by settlers on Lasqueti Island, this book tells the stories of hippies, back-to-the-landers, and draft dodgers who farmed and lived on the land communally throughout the 1960s and 1970s. The narrators’ reflect on their younger days on the island, building shanty houses on the beach, playing music, smoking weed, and trying to build a community hall. The residents faced many legal problems due to their lack of citizenship and illicit substance production, and effectively became scapegoats for many of the region’s community concerns. A central thread throughout the stories is that of prohibition. During the early days as a logging colony, an infamous Lasqueti island resident produced moonshine to sell to locals, until he was entrapped and arrested, a story widely told on the island. The back-to-the-landers grew weed and faced similar legal difficulties, including police raids, which were often fairly half-assed and rarely resulted in arrest. Lasqueti island hippies gained a bad reputation among the townships of Parksville and Qualicum Beach, despite their resounding qualities–hard work, an inspired sense of justice, and chill vibes all around. The book is a testament to the importance of oral histories–many of the stories recounted in the book are word-of-mouth legends of the era–and the contribution of oral histories to community legacy. It made me want to take a bike trip to Lasqueti carrying only this book, and tour around the old communes, farms, and the prickly pear grove.

Further Reading / Listening / Thinking

Nan Goldin’s Statement on the Purdue Pharmaceuticals Case against Sackler family

Crackdown Podcast with Garth Mullins

Harmony Holiday, Heroin as a Rhythm

THEORY IN PRACTICE: December Letter from Literary Arts

Sacrificial Cabbage

[excerpt from a conversation between Julia and Greta]

In the garden beds, purple and green cabbage grow for winter, soon to be harvested and pickled for kraut, eaten with salted fish and beet soup, if only they last the season.

Slugs!

Have you tried copper netting?

Have you tried marigolds?

They crawl up the raised boxes?

Maybe you just have to sacrifice one cabbage to the slugs, so the others can grow?

Taking its name from a garden plant ravaged by slugs, Sacrificial Cabbage was a workshop series hosted throughout the month of November that invited contemporary artists to share their practice with our regional community. Artists Christina Battle, S F Ho, and Tania Willard facilitated workshops on ecology, seed saving, medicinal plants, and land-based practices that engaged broader dialogues around climate change, disaster capitalism, land and food sovereignty, and harm reduction. Together we read, wrote, cut and glued, talked about the weather (no longer a banal topic), and stepped outside to pay attention to what was around us. We thought about our needs as a group and as individuals, how to sustain ourselves and our communities, and how to foster reciprocity with the lands we live on and the communities we live in.

Core to the Sacrificial Cabbage programs was the notion of maintenance. Drawing on Mierle Laderman Ukeles Maintenance Art Manifesto (1969), and the labour of maintaining the ecosystems we tend to every day, the workshops sought to reframe our relationality to plants and non-human beings. Julia’s anecdote about the slugs in the cabbage inspired a dialogue about attempts to mitigate the damage of aphids, slugs, deer, and other pests in the garden with companion planting, copper netting, and fencing. These tips are helpful to an extent, but what happens if we adjust our attitude towards pests, and forge a more generative relationship with the bugs, animals, and microbes that live in our gardens? When we adjust to a practice of reciprocity, can we also resist the idea of scarcity and private property for the sake of abundance and community? These questions were central to the workshops, as participants were invited to explore their relationship to the weather, medicinal plants, and outdoor spaces beyond their computer screens.

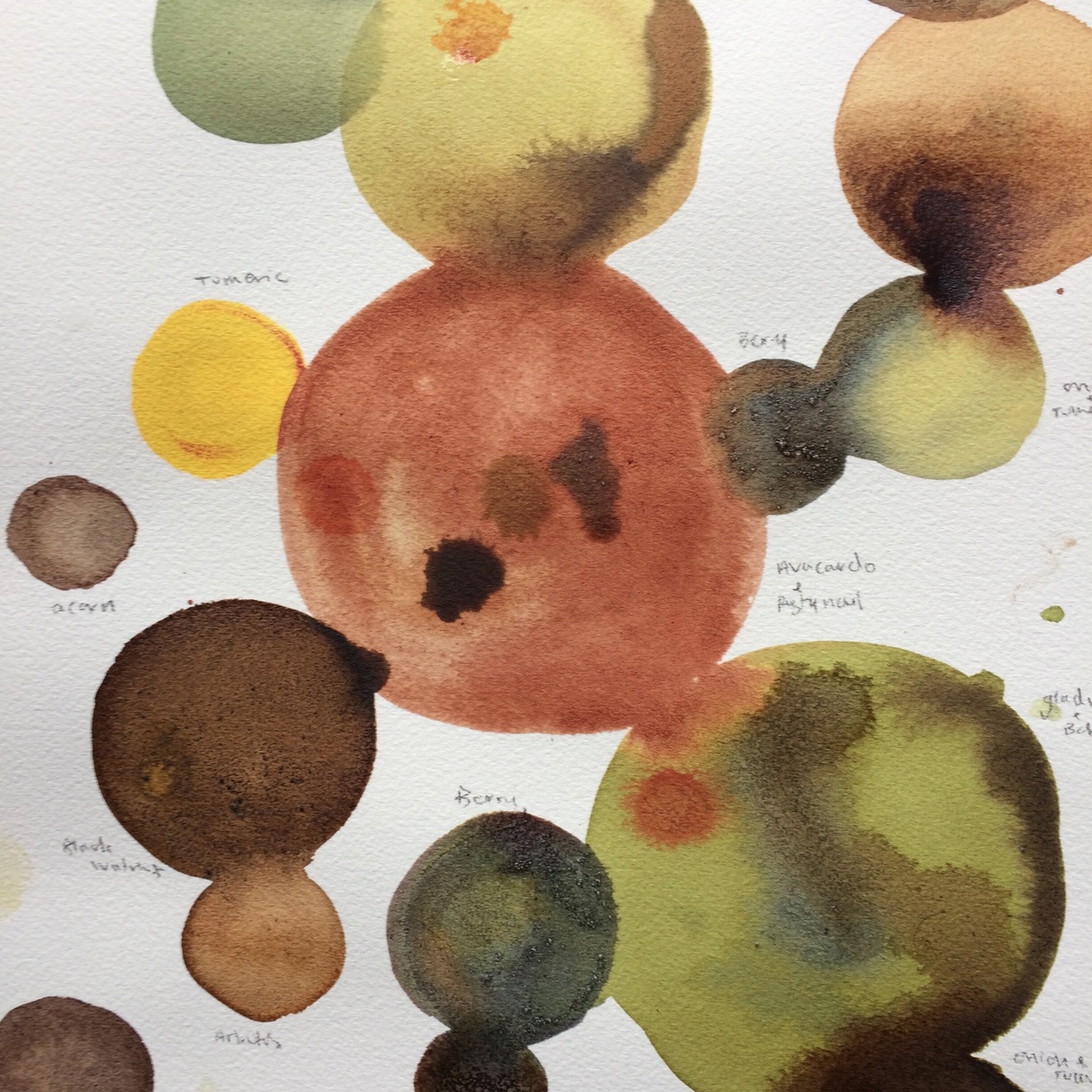

Christina Battle’s workshop was rooted in her practice as a media artist engaged in participation and the notion of disaster as a site that generates dispersed systems of care and knowledge. Battle mailed a package to workshop participants with seeds, chamomile tea, a beeswax candle, collage materials, and charts with colour and smell descriptions. Participants filled out a form about the weather (part of an ongoing research practice for Battle), read texts by Natasha Myers and Zadie Smith, and discussed the effect of shifting meteorologic patterns on gardening, seed saving, and soil regeneration–all while collaging postcards to send each other as a reminder to plant the seeds come spring.

S F Ho led a workshop that troubled perceptions of plants as healing or toxic, with a particular focus on the geopolitical histories of poppies as a medicinal plant and drug. Ho read from a milky new work that positions their familial lineage and experiences living as a settler in Vancouver within the histories of poppies and opium trade. They spoke about vernacular healing modalities and traditional Chinese medicine in relation to their grandfather’s zine making and apothecary. Participants were invited to read and write collectively in response to prompts Ho provided around plant medicine, health, and sustenance. The workshop ended on a musical note, as Stevie Wonder’s “The Secret Life of Plants” played us out.

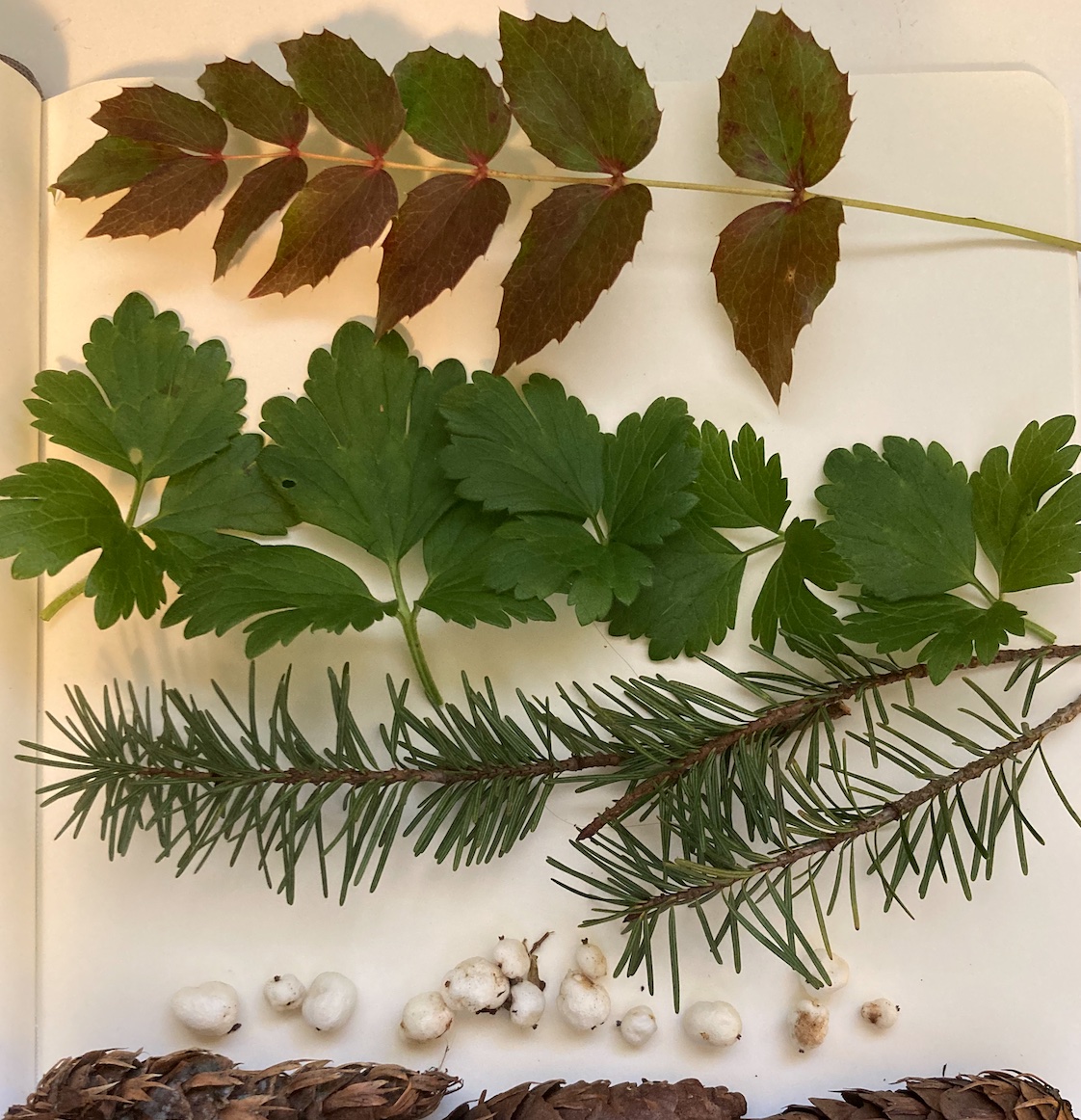

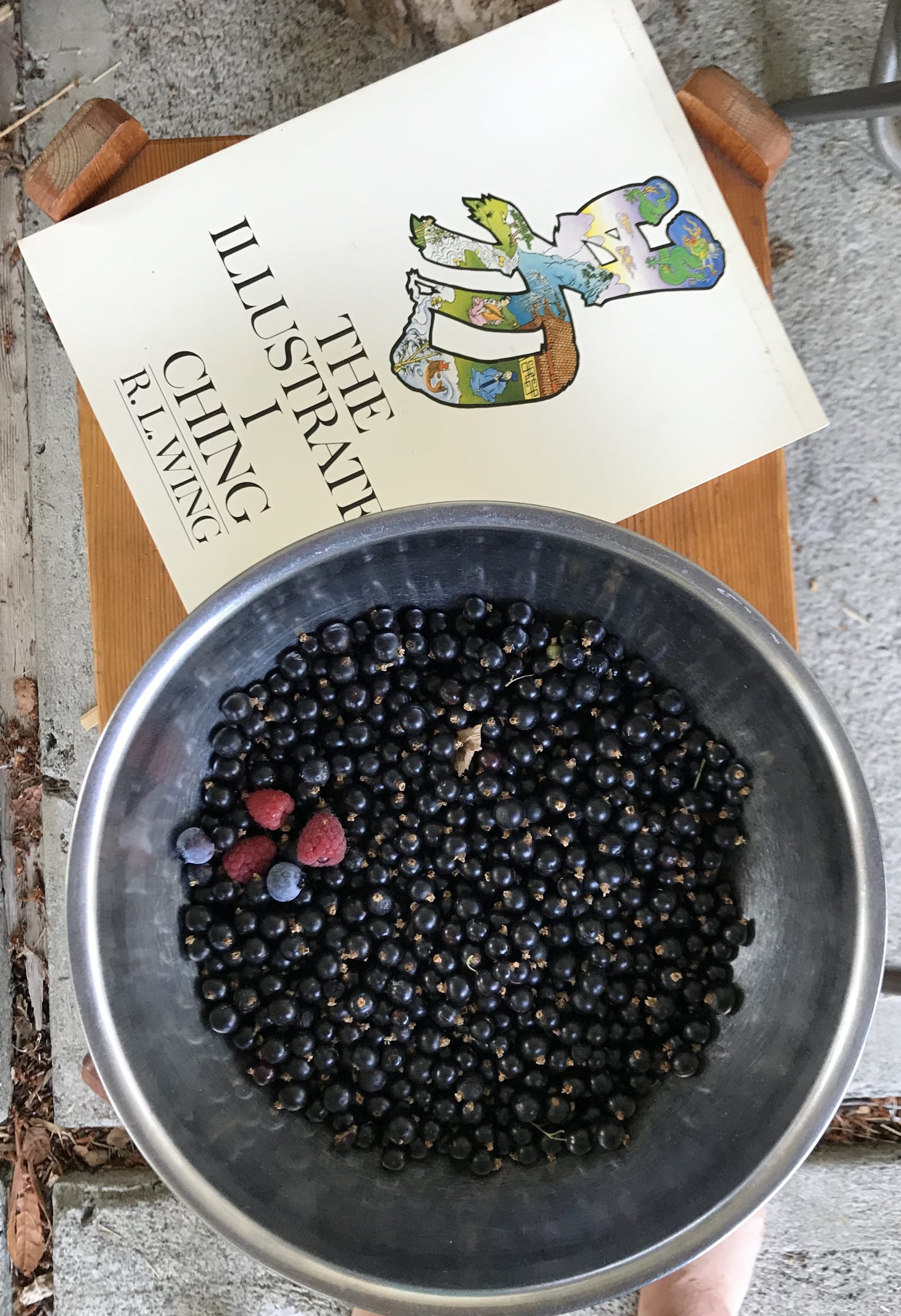

Tania Willard spoke about the shift in her curatorial and artistic practices when she became a mother, and relocated to her family’s rural reserve land. Willard sought to engage intergenerational and non-human collaboration and Indigenous epistemologies within a contemporary art space. Thus emerged BUSH Gallery, a rural outdoor gallery and collective activated by Willard and collaborators Peter Morin, Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill, and Jeneen Frei Njootli. Through the happenings at BUSH Gallery, Willard developed a practice of site/ation, a collage based citational practice that acts as both a land acknowledgement and storytelling device. Willard invited participants to step outside to gather plants, berries, snow, twigs, anything that inspired a memory, story, relationship, or place of learning from the land. The result was a series of citational collages that initiated dialogue around our relationship to the places we live.

Soon to emerge from the Sacrificial Cabbage workshops are three broadsheets that offer readings, references, and notes to summarize the happenings of the workshops. Inspired by newsletters and broadsheets produced by communes and by anarchist printing presses, the broadsheets attempt to create a sustained system of knowledge dissemination invested in collective nurturance, resistance, and dreaming. The broadsheets will be available for pickup onsite at Oxygen Art Centre, or mailed out by request. Email literaryarts [at] oxygenartcentre [dot] org to request one (or three).

dig a hole in the garden

A new initiation of theory and practice, dig a hole in the garden is a three phase research project that begins with monthly blog posts on SALT VERY IMPORTANT, and will culminate in an exhibition at Oxygen Art Centre in June 2022. The project engages slowness and adaptability in contemporary art practice. Inspired by methodologies of slow curating and queer temporalities, dig a hole in the garden attempts to initiate a state of transformation in the gallery through exhibition and public programs.

This phase of research collects cultural references, images, songs, states of being, and emotions that inspire the aesthetic and critical ambition of the exhibition. At the moment, dig a hole in the garden, is inspired by slime, sleep, sticky fingers, adaptation, the water bears (tardigrades) that landed on the moon, Freak Heat Waves, heal your powerful mind sleep podcast, hay bale furniture, resin, caterpillars, slug sex, butterflies, Derek Jarman, hibernation, habitation, arousal, the fish at the bottom of the pond in the winter, inertia, momentum, space vacuums, black holes, dark matter, aura photographs, heat sensitive wall paper, candles, transition, rurality, fermentation, gestation, My Year of Rest and Relaxation, stoner chill, vibeology, winter gardens, sand mandalas, pet rocks, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, dormancy, elongation, bean bag chairs, vernacular architectures, the opposite of a fidget spinner, exhaustion.

Notions of adaption and hibernation will be explored as responses to crises both biological and ecological. To face mass extinction, water shortages, monoculture crops, floods, wild fires, earthquakes, viral pandemics, and the myriad contemporaneous crises of our moment. dig a hole in the garden seeks to explore these transitions through the messy osmosis of ecosystems and humans.

ELEMENTS OF A COMMUNE: August and September Letter from Literary Arts

“Communes are a movement in consciousness.” Getting Back Together, Robert Houriet, 1971

After thinking through communes as a form of refusal–that is, the conscious dropping out of society and mainstream culture/consumption for the formation of self-organized communities–I wondered: Is there a life affirming form of refusal? It seems so often that refusal comes at the cost of our bodies, of social ease, or the fullness of our lives. When we drop out of what’s considered mainstream or normative culture, we lose a certain ability to move through that culture, to access and participate in it, often resulting in lack of access to health care, goods and services, and public space. It is in the loss of dropping-out where revolution becomes possible, and at the same time, creates a longing for something easier. How does one balance the desire for ease with the simultaneous need and desire to fight capitalism, colonialism, private property, and the necropolitical criminalization of drugs and poverty? Can refusal be life-affirming, or must it always come at the cost of social alienation?

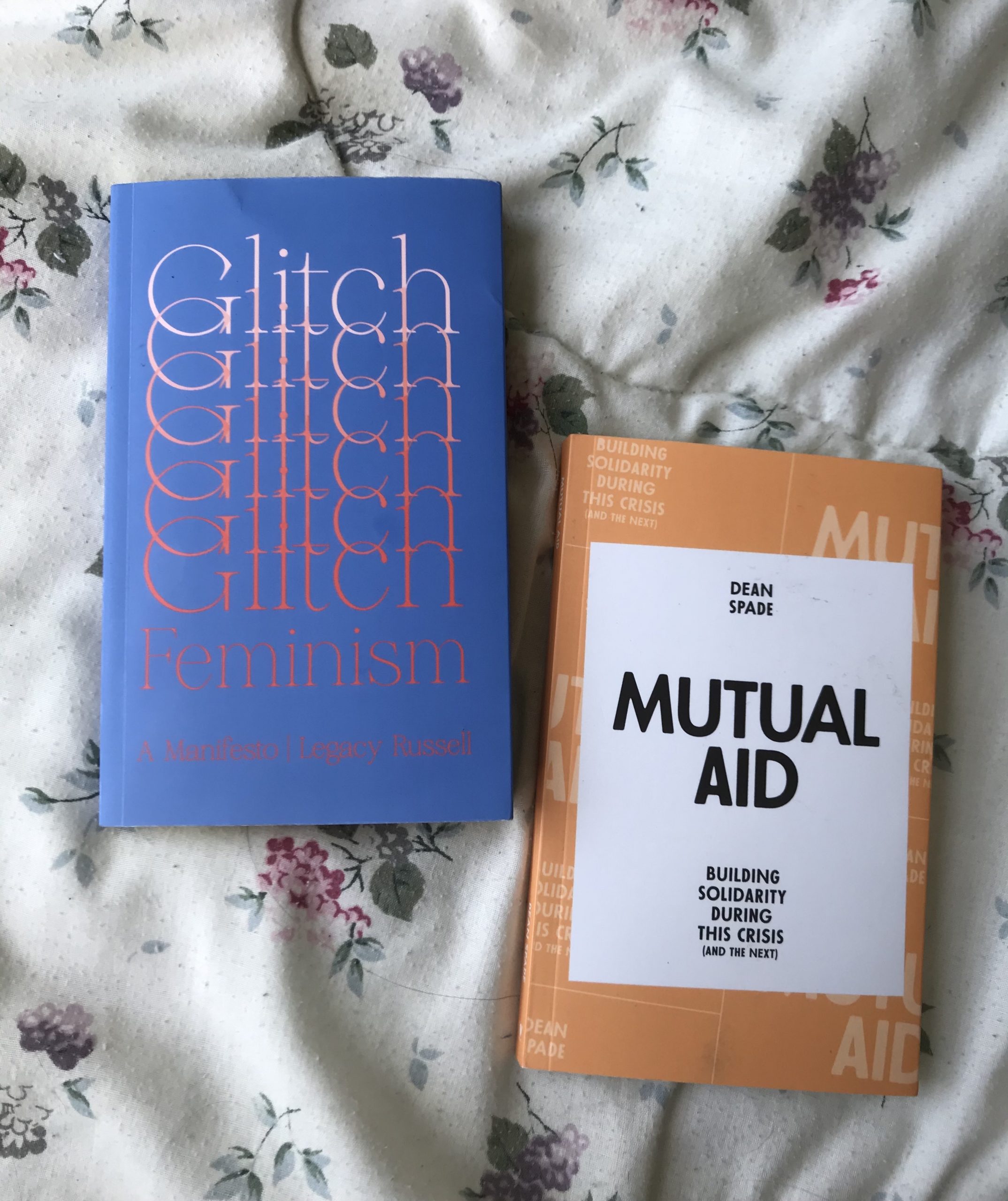

Through August and September, I read Getting Back Together by Robert Houriet (1971), Communes in the Counterculture by Keith Melville (1972), Mutual Aid by Dean Spade (2020), and Siddartha by Herman Hesse (1922). Both Houriet and Melville’s accounts of communes come from the era in which the counterculture began. While Melville describes the counterculture through a critique of capital, Houriet’s insights are more personal. In Getting Back Together, Houriet travels between California, New Mexico and Vermont visiting communes in their early days, sites that were organized on the basis of self-sufficiency, farming, organic eating, consensus decision making, and sometimes mysticism, drug-use, and polyamory (then dubbed Free Love). Houriet provides insight into the origins of the communal movement, the day-to-day happenings of communes, and especially, what kept them together. He notes the importance of a shared ideology, be it political or spiritual, in keeping a commune together. He describes how many communes failed in their early days due to a lack of commitment by members to these sites, general vagabonding and a desire to escape practicality. Houriet underscores how necessary income, labour, and collective propriety were to the maintenance of communes.

The penultimate event in the first sections of Getting Back Together, is Houriet’s confrontation with death. As he ponders dropping acid, Houriet evokes the more mystical and spiritual aspects of communal life. In visiting various communes, Houriet witnesses spiritual transformation and salvation by commune members who seek guidance from gurus and spiritual leaders at these sites, communes that practiced new age techniques, Christian mysticism and paganism. All the while, he carries his tab of acid in his pocket. When finally he takes the tab, he reckons with himself, suffers what he deems an ego-death, an experience that becomes inextricable from his understanding of communal life. That one must give in and give up their self-hood to fully be there, to participate.

After I read Siddartha, I noticed a similarity in how enlightenment is achieved by both characters: Some kind of ego-death–be it drug induced, meditative, deprivation, self-abnegation–is required for the characters to reaffirm their lives. This was this notion of death that made me wonder about life-affirming refusal and alienation. I’m keeping the question with me as I continue to read about communes, counterculture, the back-to-the-land movement, and more contemporary cultural and political ideations of refusal and dissent. My intuition is that the affirming aspects of resistance philosophies supersede the negation of the self, to intend towards futures that are more viable, maybe even sustainable. That the necessary death is generative. That maybe if we alter our consciousness, suffer an ego-death, there might be some radical shift in how we empathize and care for systems of life.

Other Readings

Interventions on Hostile Architecture by Benjamin de Boer and Phat Le

An Artist’s Guide to Herbs: Psilocybin by Harmony Holiday

DROPOUT PIECE: July Letter from Literary Arts

July brought sunset swims, moonlight above Arbutus trees, hugs, splendour, zucchini, the return of morning glory in the garden, library visits, and the impending change of seasons. The sun sets earlier, the grass is yellow; at season’s change I’m often reminded of what I was doing the year before. Last summer, I had just returned from Toronto to Northern Vancouver Island. The quiet of the island was a profound comfort to me after a few months in the throes of city-wide pandemic protocols and the collective anxiety of the circumstance. On the island, there was little stimulus, no one to look at and no one to be looked at by. I felt reassured by my distance from the city. As I dug up rotting rhubarb plants from my parents’ too-shallow raised bed, I thought about who I had been in Toronto, and who I might become in this new remote place. The solitude felt like a reinvention, like I had transformed by removing myself from the perceptions of the friends, community and passersby who had witnessed me in Toronto for years. Was there something more holistic or internal about personal change when it happens outside the city?

This summer, having left the island for Vancouver, I have been reflecting on those early days of privacy in my parent’s garden. I had dropped out of the city’s economy of looking and perceiving and identifying, challenging myself to be with myself rather than in front of a public. For so many people, especially queer folks, being oneself feels more possible in a place with a lot of people, people with whom to exchange glances and knowing nods of difference and similarity; for me, the current of self-hood seems to flow most naturally when I’m not being looked at at all. I’m reminded of artist Lee Lozano’s General Strike Piece which began in 1969, wherein Lozano effectively dropped out of the art world. Lozano was a conceptual artist who practiced at the precipice of art and life, her work taking on the weight of her existence through her temporally exhausting efforts. Lozano’s General Strike Piece is an instructional work, a common form of the era that offers instructions to the reader and are sometimes enacted by the artist. In Lozano’s case, she always enacted the instructions, notably in “The Halifax 3 State Experiment” at NSCAD in 1971, wherein she gave a lecture three times, once sober, once stoned, and once on acid. General Strike Piece was earlier in her career, during which she boldly refused to participate in the art world. The piece reads, “GRADUALLY BUT DETERMINEDLY AVOID BEING PRESENT AT OFFICIAL OR PUBLIC ‘UPTOWN’ FUNCTIONS OR GATHERINGS RELATED TO THE ‘ART WORLD’ IN ORDER TO PURSUE INVESTIGATIONS OF TOTAL PERSONAL AND PUBLIC REVOLUTION. EXHIBIT IN PUBLIC ONLY PIECES WHICH FURTHER SHARING OF IDEAS & INFORMATION RELATED TO TOTAL PERSONAL AND PUBLIC REVOLUTION.”

Lozano’s positing of a revolutionary life outside the typical economies of art world schmoozing, inspire me to question the meaning of being an artist, its importance (or not) in the world, and how at odds the process of creation can feel to the administration required by a career in the arts. In the city, there’s constant need to make oneself public, or to be visible in the “art world” as Lozano puts it, which can often feel contradictory to living and making work as an artist. Lozano proposes dropping out as a revolutionary gesture–that in refusing to make yourself visible, you might be free to cultivate an intellectual practice that can be brought into the public for the means of revolution. Is there some tension here then between the rural and the urban, the public and the private, the normalcy and the revolution? Lozano’s General Strike Piece puts into question the need for visibility and legibility in the arts, and how personal investigations come to take on public and political meaning, and even whether or not they have to? What would it look like for artists, writers and cultural workers to collectively strike against the conditions of labour in the arts that require ‘presence at uptown functions,’ as Lozano suggests? What would change if artists dropped out, became revolutionaries?

As these questions come up for me, and as I continue to read about feminist, queer, lesbian and trans people on communes, I wonder about the connected desire to drop out from gender, cities, and work, and to make oneself illegible within an identity or mode of living? These questions are taken up by Legacy Russell in her manifesto Glitch Feminism (2020) wherein she describes a generation of feminists whose online experiences formed their relationship to gender, sexuality and race identities. The short book is a cyberfeminist manifesto that proposes the glitch–or error, disappearance, illegibility–as a generative site for feminist recourse. Russell discusses contemporary digital art practices and new media works through the lens of identity politics, emphasizing how particular artistic practices draw on the glitch to centre trans and non-binary genders, which is a mode of feminist thinking that, I think, attempts to abolish the gender binary. The manifesto proposes an existence of in-betweenness, wherein identities are forged through or as the glitch, as varying parts of our experiences shape the fluid existences we inhabit both online and AFK (away from keyboard).

I’m interested in Russell’s notion of the glitch as an entry-point into gender, particularly as it relates to queer, trans and non-binary gender identities. I’ve often wondered about transness and non-binary gender as a mode of illegibility, a queering of the gender binary that opens gender towards a fluid in-betweenness, wherein an identity comes and goes, or might otherwise be (re)invented by the self infinitely. In this notion of gender as fluid, there is a certain kind of refusal or dropping out that’s necessary. These kinds of alternative modes of conceiving of gender through the glitch, remind me again of the digital utopianism proposed by early commune settlers and counterculture revolutionaries. In both Russell’s manifesto, and in the hopeful attitudes of back-to-the-landers, technology, and eventually the internet, proposed a kind of radical equity wherein universal access is possible within, and despite, how somehow identifies. Though this has been proven false in practice as technology and the internet have become independent bodies of discourse that dominate politics and create microcosmic echo-chambers of identify based groups, I think there remains something interesting and utopic about the notion of refusal as revolution. Only now the question of dropping out includes removing ourselves from the internet, which had once for back-to-the-landers been the hopeful mode of resource sharing that would allow more universal access to the knowledge and tools required to live off the land.

Russell’s Glitch Feminism offers the first in what I can only imagine will be a huge number of feminist and literary manifestos published by writers who grew up intimately with the internet. It offers a way out of the hegemonic structures of social media by imbuing digital mishaps with a kind of political potentiality. But I always wonder, despite the all or nothing perspective of this thought, what it would be like to give it up all together–the city, social media, an identity. While I think identity not only gives meaning to our lives, but through the specificity of language, can acknowledge certain histories and material conditions that continue to affect our lives, I wonder whether or not an identity can change the conditions of existence towards something more equitable. Would choosing not to identify be a futuristic mode of imagining the fruits of gender abolition? Or are the categories of identity still necessary to rectify the wrongs of the past?

And as always, a pointing-to to end the month’s thoughts. A diffuse reading group called Bread, curated for Virtual Care Lab by Aden Solway and mama collective in Tkaronto/Toronto; a poetry workshop called God is Not a Metaphor facilitated by Angelic Goldsky through ReIssue Publication’s Free School in Vancouver; Peripheral Review’s Summer Reading Series every Sunday throughout August, which was hosted by Fan Wu in its first iteration last week; the summer issue of C Magazine “Community” is out now; and a little bit more about Lee Lozano’s influence on contemporary art here.

SEEKING COMMUNE STORIES: June Letter from Literary Arts

In the aftermath of the heat dome, my thoughts are ungathered. The bathroom, once visited by silverfish, is now infested with spiders, some of whom nest together in a web by the ceiling (another Vancouver polycule, I think). The others scurry up the side of the tub when I run a cold shower to clear my head. The heat reminds me of past year’s dystopian conditions–the sun glowing red in the hazy sky, smoke drifting North from California fires. Though we have not yet arrived at the height of summer wilting–really, we’re just entering the sweet growth of pea blossoms and tiny green tomatoes–the heat dome and burning towns across BC remind me of what’s to come.

Though I have always felt enlivened by heat, I’m fearful of the possibility that these thirty and forty degree temperatures might become permanent. It’s a bleak possibility that the ecocidal predictions of science fiction novels could be realized–birds dropping dead from the sky, pollinators extinct, air conditioned glass domes built over cities of the rich. I feel listless with complacency, and compelled to refocus that sensation. How can we care for each other within the intensifying cycles of weather, heat, life and death? Community organizers like Mount Pleasant Mutual Aid have placed coolers at parks across the neighbourhood for residents to take or leave a drink; Local Open Access Fridge is installing a freezer, fridge and pantry in the Hastings-Sunrise neighbourhood for food insecure residents. Community centres, libraries and gyms have become cooling stations for those without air conditioning or other cooling means. The precarity of shelter, food, and health were urgent crises prior to and during the Covid-19 pandemic, and persist as covid restrictions are lifted.

Much like in the early days of the pandemic, this month felt like a moment to reconsider the role of artists, writers, and cultural workers within community care and activism. How can the work of art writing, criticism, and art making, translate to community problem solving? I think one of the tasks of cultural workers is to promote and maintain a culture of sustenance, one that uplifts the well-being of one’s neighbourhood. In Toronto for example, many artists and cultural workers organize with the Encampment Support Network to protest encampment evictions, provide unhoused residents with water, and work on the podcast We Are Not the Virus. In the vein of thinking through the role of artists and writers in community care, I want to mention a couple of my reads this month that generated some of these ideas.

Outdoor School is a new book of contemporary environmental art edited by Amish Morrell and Diane Borsato. I attended a lecture with Morrell and Borsato hosted online by Doris McCarthy Gallery in Scarborough, ON. The editors foregrounded the role of artists as teachers and keen observers of their environment. Morrell and Borsato envision artists as those sharing with the world what might not otherwise be seen–artists look into nooks, see the invisible, and tell forgotten stories. Included in Outdoor School is the BUSH Manifesto, created by Tania Willard, Peter Morin, Jeneen Frei Njootli and Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill. Bush Manifesto calls for an artistic and critical site outside of the gallery, a land based practice where bears, dogs, children and grandparents are welcome in the actions; “BUSH Gallery…contributes to an understanding of how gallery systems and art mediums might be transfigured, translated and transformed by Indigenous knowledges, traditions, aesthetics, performance, and land-use systems.”

Also in Outdoor School is an essay by environmental philosopher Karen Houle. In “Farm as Ethics,” Houle reflects on her pedagogical practice using urban farming at Guelph University as a tool for student learning. She confronts the misogyny and cognitive/emotional dissonance of Western philosophical practice, and forges instead a holistic methodology that uses agricultural and outdoor sites to teach, learn, and heal collectively with her students. Outdoor School is an invitation for artists, writers and cultural workers to shift towards the outdoors, to cycles of life, porous practices, reciprocity with the environment, and a public intellectual culture outside of artistic and academic institutions. I should mention as well that Amish has been a mentor and friend of mine over the years, whose knowledge of communes, conceptual art and counter-cultural publications inspired much of the work I completed in my undergrad, as well as this project with Oxygen.

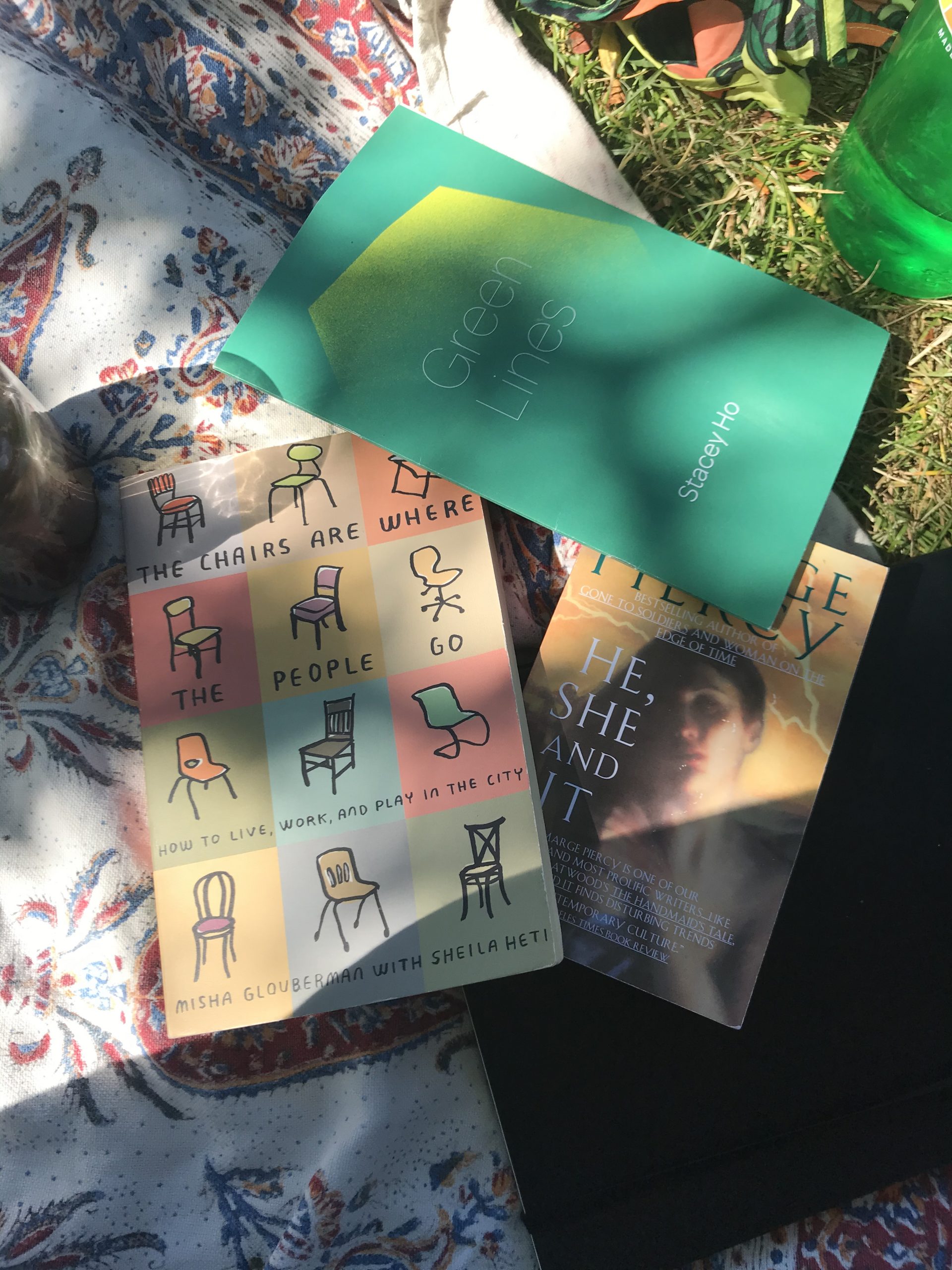

As I battled with the Himalayan blackberry and bindweed in my garden, I read Green Lines by Vancouver artist S F Ho, a chapbook that troubles the notion of invasive ecology and forges a lineage of decolonial gardens. Throughout Green Lines, Ho considers the relationship of invasive plants to politics of alienation, capitalism, and decolonial ecology. They note that both the Latin and English proliferation of plant names “render plants ahistorical” by erasing the uses carried by their native or colloquial names. Ho also notes that while invasive plants are named for where they’re from, “Himalayan black berry, Scotch broom,” what makes them invasive is not their foreignness, but their potential to limit capital; “a plant becomes a weed when it threatens intensive farming and industrial agricultural practices” and thus, when it threatens white, Western, capitalist culture. The bibliography in Green Lines is also an enriching starting point for readings on anti-invasion ecologies. Ho cites My Garden by Jamaica Kincaid, and the decolonial garden at 221a semi-public led by artist T’uy’t’tanat-Cease Wyss.

In the realm of upcoming business, the Slocan Valley’s independent newspaper, The Valley Voice, is for sale! Though we dreamed momentarily of acquiring the publication, instead I offer our brief personals listing:

SEEKING COMMUNE STORIES: Do you live communally in the Slocan Valley? Have you been part of a commune, organic farm or free school? Would you like to tell your story? Oxygen Art Centre is seeking commune dwellers to contribute to a research project that maps the history of communal living across the Slocan Valley and BC interior. If you would like to be interviewed about your experience, please email Greta at literaryarts@oxygenartcentre.org

And a couple viewings/readings of note for the month: Derya Akay’s Meydan at Polygon Gallery in Vancouver can be viewed until the first of August; the Contingencies of Care conference, hosted by OCAD U throughout the month of June, is recorded and available online; and UK based artist Sean Roy Parker’s newsletter, Fermental Health, is very good!

THE DAY WILL COME WHEN WE WILL HAVE TO KNOW THE ANSWERS: May Letter from Literary Arts

I’m penning this letter on a hot day with morning sun, shag carpet, Beverly-Glenn Copeland singing in the background, hibiscus tea cooling on the stove, and peeking out the window at the dye plants on the patio–the Indigo particularly bushy and needing repotting. This letter, and these letters (will), emerge from the contexts in which I am working across various small towns, islands and rented apartments in BC over the next ten months, conducting research for the new position Literary Arts Coordinator at Oxygen Art Centre. This project emerged through a shared desire between myself and Julia to develop a publication that took up the ethos and aesthetic of counter-cultural publications of the late 1960s and 1970s, including the Whole Earth Catalogue, Mother Earth News, Radical Faerie Digest, the New Woman’s Survival Catalogue, and the many independently published broadsheets and newsletters of that era, each offering various survival skills and DIY resources for rural women, queers, homesteaders, and organic farmers. We also bring together our individual bodies of research–Julia’s studies in feminist practices of curation across rural locales, and my desire to excavate a personal history as the child of a back-to-the-lander and wannabe-organic-farmer father.

We conceptualized the project a number of months into the pandemic, a moment in which many communities were organizing towards a shared sense of survival across multiple crises. We wondered what a contemporary revival of counter-cultural publications might look like, what resources most urgently need textual distribution, what issues remain unchanged. Through the coalescence of our research questions, we are attempting to develop a publication that deepens our understanding of the counter-cultural revolution’s failures and takes up its potential points of renewal. SALT VERY IMPORTANT is one such research aspect of this project.

In developing a publishing project that draws on counter-cultural and revolutionary texts, we are asking the following questions, among many: Why did the dream of co-operative land ownership, Buddhist economics, free love, and agricultural freedom fail in the face of neo-liberal capitalism and the personal tech industry? Why was the emergence of a mass cultural turn towards anti-racist, anti-capitalist, anarchist/anti-government, and feminist practice depleted by the end of the 1970s? Because the Whole Earth Catalogue was considered a precursor to the internet, what is the connection between the digital utopianism of 1960s California hippies and the contemporary tech dystopia currently unfolding in Silicon Valley? How can we continue to learn from counter-cultural thinkers while remaining critical of the back-to-the-land movement’s whitewashed and colonial concept of a “return” to nature? How do we acknowledge and honour the back-to-the-land movement’s debts to activists organizing around mutual aid and anarchism? How does the ethos of counter-culture fit into contemporary movements like Black Lives Matter and Land Back? What are some alternative histories that can decentre whiteness from organic farming, communal living, and our relationship to the outdoors?

These aren’t rhetorical questions, as so often questions are when posed in the arts. This project will forge ahead to answer these questions through traditional archival research, alongside more material processes like conducting interviews, visiting gardens, farms, and compost centres, and maintaining the methodology of an eco-feminist practice (whatever that might look like to me these days; I’m thinking about my dye plants on the patio again). Through the coming months, I aim to develop infrastructure and resources for a long-term educational program and publication at Oxygen that picks up the threads of the counter-cultural vision within the context of contemporary anti-racist, decolonial, and feminist practices. This might include reading lists, an interview series, print and publishing workshops, as well as creating a publication by and for rural artists and writers across BC. These letters, too, act as a form of institutional transparency, as I describe the changes and malleability of this project over time. (The letters also borrow the title from Diane Di Prima’s Revolutionary Letter #3, the line, “SALT VERY IMPORTANT,” and this month’s title from Revolutionary Letter #6, “None of us knows the answers, think about / these things. The day will come when we will have to know / the answers.” Published 1968).

Alongside this research aspect of this publishing project, I’m spending some time considering what the tasks of a Literary Arts Coordinator are within an artist-run-centre, and what they could be. To name a few possibilities I’ve noted over the last month: to create financial and community contingency for the current literary projects including the author reading series, and the publication of artist monographs and exhibition catalogues; to develop educational programming on print practices and publishing; to acquire a library of artist books and multiples, as well as texts and publications relevant to the centre’s programming. While it may not be me who develops these resources in their entirety at Oxygen, I’m planting the seeds here.

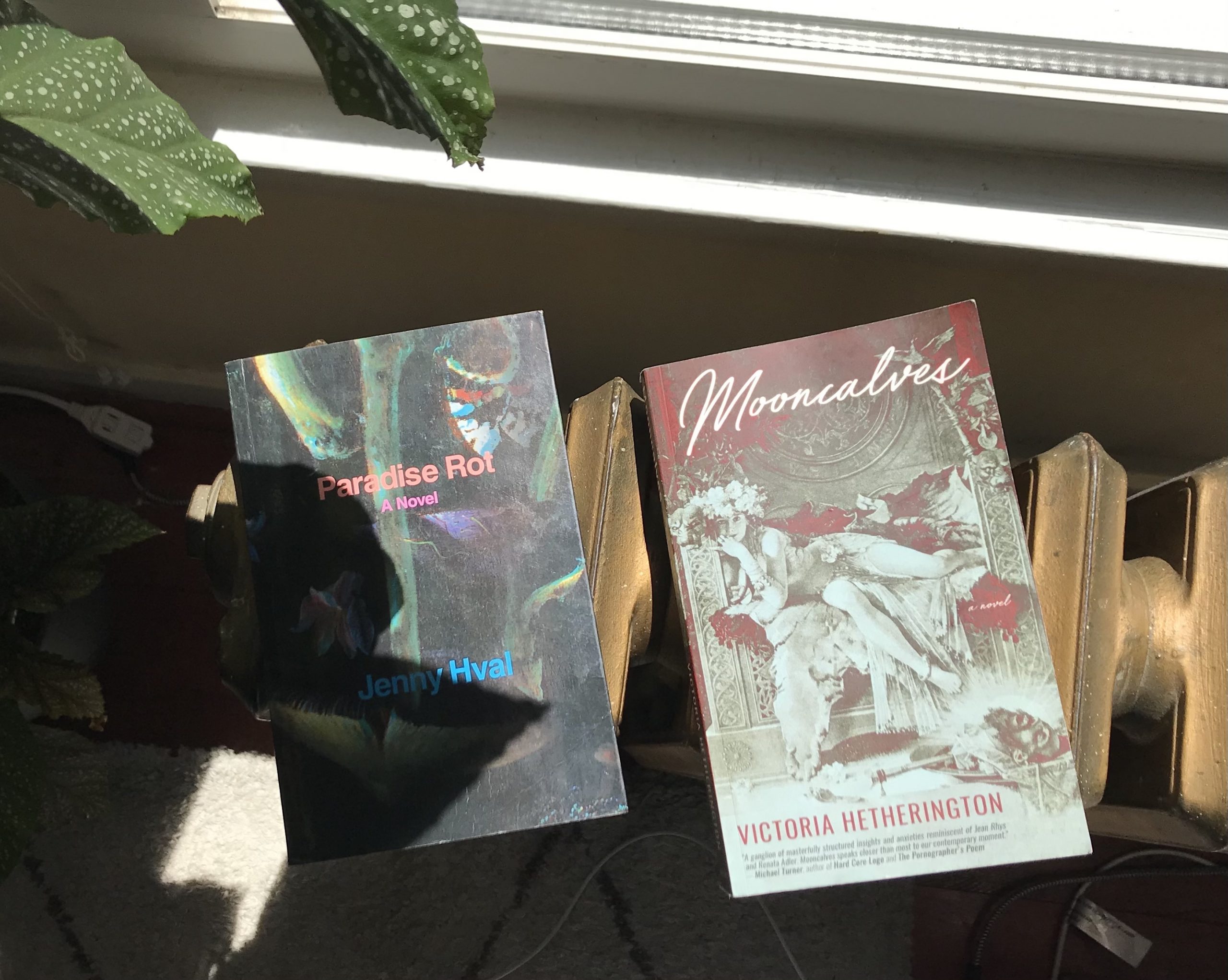

This month I split my time between researching grants to develop a publication and educational programming for the upcoming year, compiling a reading list that includes texts ranging from conceptual art, to climate change, to the tech industry, and attending workshops on farming and co-operative land ownership. I had a short visit with Garden Don’t Care at Unit 17 in Vancouver. I attended the virtual launch of the Centre for Sustainable Curation at Western University with a panel on Curating and Radical Pedagogy including panelists Christina Battle, Gabby Moser, Ryan Rice, Eugenia Kisin, Tania Willard and Christiana Abraham. I also attended the virtual panel Doing the Work: Art and Activism at McMaster University, which featured short talks by Syrus Marcus Ware, Jenna Reid, and Ravyn Wngz. I read Paradise Rot by Jenny Hval, Mooncalves by Victoria Hetherington, I revisited the Maintenance Art Manifesto by Mierle Ukeles Laderman, and the first issue of MICE Magazine on Invisible Labour.

Want to get in touch? Have a story you want to tell? Want to contribute? Email Greta at literaryarts@oxygenartcentre.org